Text and photos by Pavel Petrov, EKA

Gregor Taul opening the final session of the workshop at the Estonian Academy of Arts where five groups of the participants presented results of their case studies on contested heritage in north-eastern Estonia

In response to the global conversation on contested heritage, sparked by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA) organised an international workshop from 31 August to 6 September 2024 in Narva and Tallinn. The workshop, titled “How to Reframe Monuments – Case Studies for Thinking through Dissonant Heritage,” was held in collaboration with the Transform4Europe partners Vytautas Magnus University (Kaunas) and the University of Trieste. Narva Art Residency (NART) served as the primary venue for the event, which focused on five case studies in northeastern Estonia. The program included lectures, seminars, guided tours, group work, fieldwork, and a documentary screening. It brought together international experts and students from various fields to develop new approaches to Estonia’s complex heritage with potential application elsewhere.

Gleb Kuznetsov of the Narva Art Residency introduced workshop participants to the complex history of the building. From an industrial managerial residence in the late 19th century, the house evolved into an international hub for arts and local culture at the Estonian-Russian border.

Scholars, artists, and professionals from different disciplines gathered to share insights and oversee the case studies. Around thirty bachelor’s and master’s students from across Europe, representing diverse backgrounds in arts, heritage, history, architecture, design, and IT, were divided into five interdisciplinary groups. They worked on case studies involving the removed Lenin statue in Narva, the Püssi ash hill, a discarded metal ornament from the Auvere power plant, monument to the Kreenholm Strike of 1872, and Soviet Second World War memorials in Sillamäe.

Denis Girenko, urban artist of Narva, guided the workshop participants through the local heritage landmarks. The now-decaying Vasily Gerasimov culture palace was dedicated to one of the organisers of the strike at the neighbouring Kreenholm Textile Manufacture in 1872. Memory of this major political event, labour movement, and associated persons are still present in today’s Narva, spatialised in topography and several monuments with one of them studied at the workshop

The first day began with a tour of NART’s building, a historic villa once built for the director of the Kreenholm Textile Manufacture. Kreenholm’s fascinating history reflects the complex past of both Narva and Estonia since the mid-19th century. Students were introduced to one another during group brainstorming sessions.

Amalie Kreisberg, an activist and martyr of the labour movement in Estonia, is commemorated with a classical sculpture against the eye-catching Soviet modernist mosaic background. Employed at the Kreenholm Textile Manufacture, Kreisberg participated in the 1905 strike demanding a shorter work day but after the arrest died in prison at the age of 26.

The program continued with an exploration of Narva’s monuments, led by Denis Girenko, an EKA alumnus and Narva’s urban artist. The group visited sites like the decaying Stalinist House of Culture of Textile Workers (1957) and the redesigned Swedish Lion monument at the Estonian-Russian border. Erected with funds from Sweden in 1936, the Swedish Lion monument commemorated the Battle of Narva of 1700. At the time, the Estonian border ran east of the Narva river. Just like most of the city, the monument perished in the final months of the Second World War. Celebrating the 300th anniversary of the Swedish victory against the Russian army in Narva, a smaller version of the monument in an adjacent location was unveiled in 2000 at what now was the Estonian border. However, instead of reproducing the original, the current memorial took inspiration from the lion statues at the Royal Academy of Arts in Stockholm that in turn were modelled after XVI century Italian sculptures. With that in mind, the contemporary Swedish Lion monument is an homage to its old and gone baroque city. In this sense, it is similar to the final destination of the first day – the Narva College of the University of Tartu whose postmodernist façade reflects the architecture of the neighbouring town hall.

Narva lost most of its centuries-old architecture layer in a few months of battles in 1944. In rebuilding and remodelling it into a modern Soviet city, some surviving older houses came to serve as a contrasting background for the bold and literally towering images of the new socialist era

On the second day, the groups visited the objects in their respective case studies and worked at NART. During dinner, participants exchanged impressions, and faculty from the organising universities joined the discussion about the workshop.

Case study groups were intensively working on their projects in the NART’s inspiring spaces, such as the room with the exhibition about the Kreenholm Textile Manufacture.

Day three started with group work, followed by a lecture from Linara Dovydaitytė, an associate professor at Vytautas Magnus University, on dissonant heritage. She introduced the key concepts of the workshop’s theme. Kristo Nurmis, a research fellow at Tallinn University, presented the Soviet memorial commemorating the Tehumardi battle (1944) in Saaremaa, which was partially dismantled in 2024. Through the How to Reframe Monuments project, EKA had been involved in reframing the memorial with pop-up exhibitions and proposals from five Estonian artists.

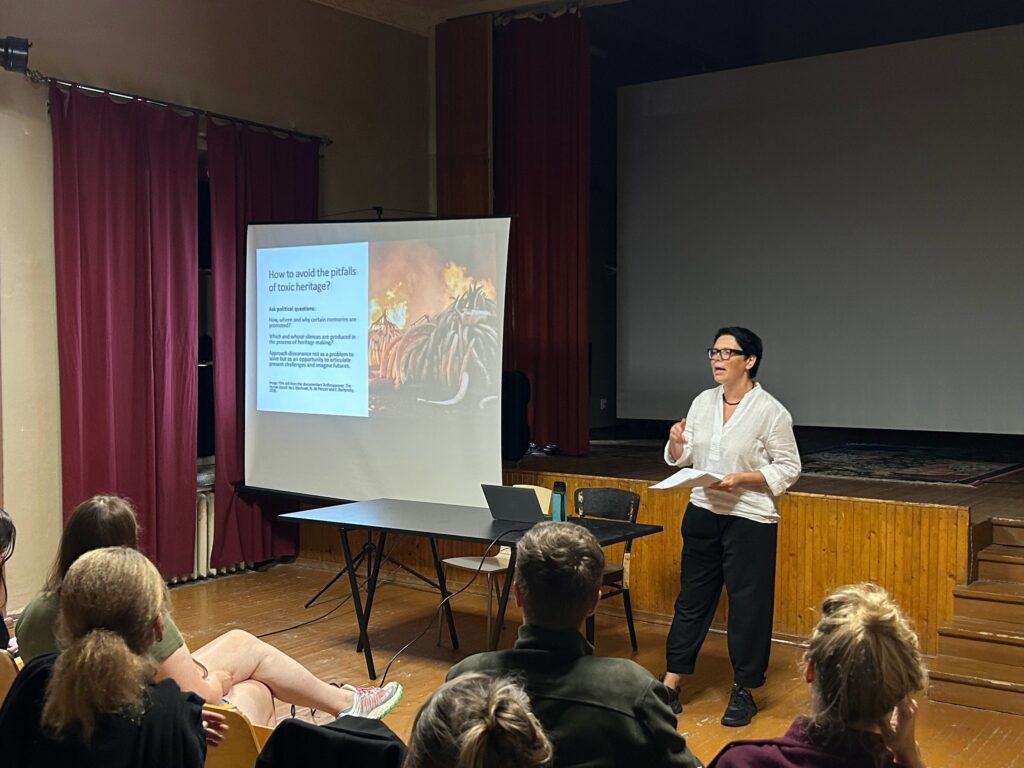

Linara Dovydaitytė delivered the workshop’s first lecture in which she introduced and elaborated on some of the main concepts and themes related to dissonant heritage

Victoria Donovan, a professor at the University of St Andrews, discussed the reframing of Ukraine’s massive industrial heritage, focusing on how the Donbas region’s industrial past transformed from “privileged memory” into “historical trash.” With references to decolonial praxis of ‘critical care’ in its variations, Donovan concluded with the current state of remembering the industrial past in contemporary Ukraine. As a case in point to professor Donovan’s topic in the Estonian context, the afternoon continued with a visit to the Kreenholm Textile Manufacture, where Denis Girenko led a tour of the defunct but once prominent industrial complex.

The now-defunct Kreenholm Textile Manufacture used to be one of the largest factories in Europe. Simultaneously, the colossal enterprise turned Narva into one of the major centres of the labour movement in the Russian Empire, demonstrated already in the 1872 strike.

During the visit to the Kreenholm Textile Manufacture, participants examined one of the workshop’s case study objects – the 1872 Strike monument. Isolated from the public in the defunct factory’s closed premises, the decaying monument still projects a powerful imagery of struggle for social and economic justice.

On the fourth day, Swedish artist Runo Lagomarsino discussed his work on colonial legacies in Sweden and Spain, followed by a presentation from Estonian artist Kristina Norman on her 2009 piece “After-War,” based on the controversial Bronze Soldier monument in Tallinn. Norman reflected on her work in the context of the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war and the current debates around Soviet monuments. In her other works, she explored links between Estonia and Indonesia through the unusual fates of Andres and Emelie Saal who ended up working for the Dutch colonial administration. Spatialisation of the difficult past was common for both Lagomarsino’s and Norman’s concepts. In Lagomarsino’s case, it was imagined via a range of performances and installations that would commemorate and re-establish connection between the Swedish coastal city of Gothenburg and the former island colony of Saint-Barthelemy in the Caribbean. Norman, on the other hand, made visible the persistent sentiments and problems surrounding the relocated Bronze Soldier by reinstalling its replica on the original site. Both artists posed their respective societies with uncomfortable questions that remain unresolved to this day.

Olha Honchar, director at the Territory of Terror museum in Lviv, explained policies towards Soviet and Russian heritage in Ukraine. Among other things, it involved extensive changes in toponymics in 2010s, but also toppling of Lenin statues, the so-called “Leninopad”.

Later lectures by Ukrainian and Italian speakers, including Olha Honchar from the “Territory of Terror” Museum in Lviv and Professor Tullia Catalan from the University of Trieste, explored reframing Soviet and Fascist legacies in their respective countries. Catalan approached her subject through the case studies of the Italian border cities of Bolzano and Trieste. Particularly, the latter presented with an intriguing example of intersection between contemporary local politics and the aftermath of the Second World War in the Italian-Slovene context. Among other things, Catalan pointed out that the engagement of the local population is essential for providing contested heritage with new contexts and thus prospects of preservation. Later, this moment proved to be central for the workshop’s case studies. The topic of Ukraine proved to be engaging too, generating a discussion that illustrated the complexity of the country’s history and its representations, but also variations in Western and Eastern European perceptions and focuses.

Tullia Catalan from the University of Trieste approached the subject of dissonant heritage from the perspective of border studies. As she pointed out, memories in border areas are often conflicted as a result of war traumas and occupations. This was particularly applicable to Trieste that experienced a brief Yugoslav occupation in the aftermath of the Second World War.

The evening lectures moved the focus back to the Baltics and their Soviet legacy. Epp Annus, associate professor at the Tallinn University and lecturer at the Ohio State University, analysed war graves in Estonian literature through the example of Juhan Peegel’s novel “I fell in the first war summer” (Estonian “Ma langesin esimesel sõjasuvel”). Military cemeteries were revisited in Kirke Kangro’s presentation about the Tehumardi memorial. Kangro contemplated inter alia on the role of artist in working with the dissonant inheritance, both in its production and deconstruction. Egle Grebliauskaite, an artist and scholar at the Vilnius University, continued to explore the role of the artist in approaching dissonant heritage. In her lecture, Grebliauskaite focused on relations between artist autonomy and political control in the context of memory transformations. Bringing together theory and practice, she discussed in detail different solutions in keeping or removing contested monuments. Her own recent intervention with the Petras Zvirka monument in Vilnius provided an apt example of addressing this issue.

What do we do with dissonant heritage was one of the workshop’s central questions comprehensively discussed by the Lithuanian artist Egle Grebliauskaite (at the table). Choosing between keeping and removal depends on the circumstances and employs a variety of solutions. Reframing being one of them could be done through an artistic intervention but relies also on public narrative

The day ended with a screening of the documentary “Alyosha” (2008) about the so-called Bronze Soldier monument in Tallinn. Following a period of increasingly agitated debates, the Estonian authorities decided to relocate the monument to Soviet soldiers from the city centre to a military cemetery in 2007. In protest to that, a violent unrest, subsequently named the Bronze Night, erupted on the streets of Tallinn on a scale without parallels in contemporary Baltic history. The screening was followed by a discussion with its director Meelis Muhu and Kristina Norman. The duo behind the documentary shared with the audiences their experiences of recording a unique visual chronicle of the violent unrests of the Bronze Night in 2007, but also peaceful celebration traditions that emerged around the contested Soviet war memorial both before and after its relocation. Spatialisation and public engagement through artistic interventions were therefore the key words and concepts of the day.

Sillamäe, a former seaside resort town with a small-scale oil shale industry, turned into a centre of Soviet nuclear technologies after the Second World War. As a consequence, Sillamäe’s appearances and demographics profoundly changed. Architecturally, it is dominated by the Stalinist neo-classicism. Similarly to Narva, Sillamäe grew overwhelmingly Russian-speaking in the Soviet period. Due to its strategic importance, access to the town required a special permit until the re-establishment of Estonian independence. Photo: Pavel Petrov, EKA.

On day five, the participants toured Sillamäe, a small coastal town west of Narva, known for its Stalinist architecture and Soviet-era nuclear heritage. Led by Aljona Gineiko, a PhD student at EKA, the group explored the town’s historical landmarks, including a Soviet war memorial. At the Sillamäe Cultural Centre, Riin Alatalu, an Associate Professor at EKA, delivered a lecture on the town’s dissonant heritage, focusing on the representation of war and its aftermath. Preliminary results from the case study groups were presented and discussed in preparation for their final work.

In Sillamäe, participants had an opportunity to take a closer look at one of the workshop’s studied cases - its Soviet war memorial to the unknown soldier (1975). Subject of a political controversy, the monument is on the list of the heritage to be removed from the public space.

After a final day of group work in Narva, the participants travelled to Tallinn for the workshop’s conclusion. They presented their findings and creative solutions during a public seminar at the EKA building, also streamed online. Many groups incorporated feedback from local communities in their presentations.

Employing an interview method, the case study group mapped some general attitudes among Narva residents towards the removed Lenin monument. More than a half of the respondents stated indifference while less than 10 percent each had a positive or negative view of the statue. One of the conclusions the group drew was that Narva residents wanted functional spaces that would reflect the city’s modern identity.

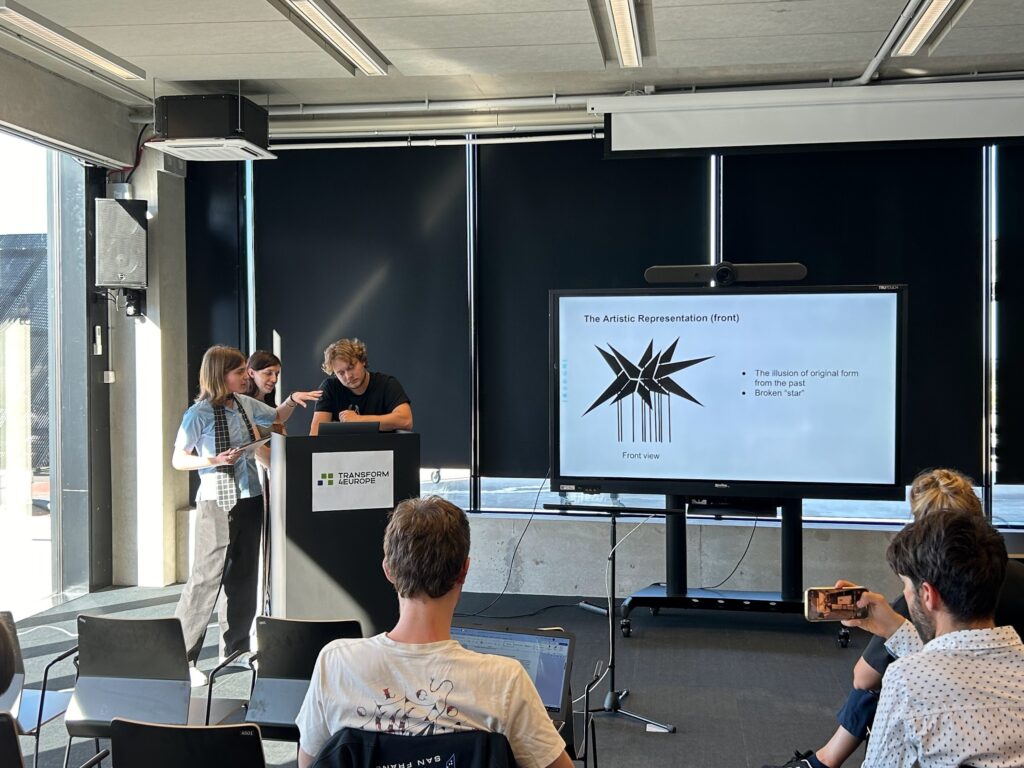

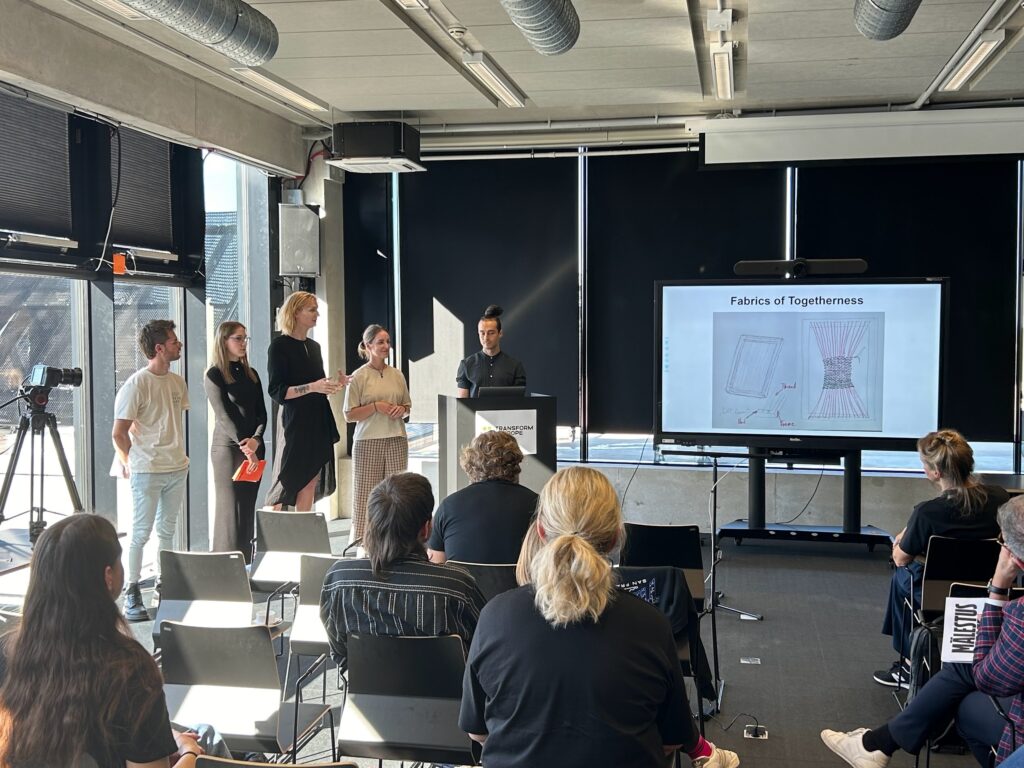

The five case studies generated visually and conceptually rich proposals for addressing dissonant heritage in northeastern Estonia. For example, the Lenin monument group suggested using augmented reality to digitally recreate the sculpture in its original location. The group studying the Püssi ash hill proposed transforming it into an interactive installation, serving as both a gathering space for the local community and a hiking site. The group working on the Auvere power plant’s ornament envisioned it as part of an open-air museum in Narva. A weaving workshop concept, centred around the monument to the Kreenholm Strike of 1872, was developed to symbolise communal unity. The Sillamäe memorial group suggested replacing Soviet servicemen portraits with mirrors, encouraging self-reflection.

Local opinions in social media and face-to-face interviews, as well as international examples, guided the case study group in addressing the issue of the Püssi ash hill. As a way of turning the table for this problematic industrial heritage, the group suggested artistic interventions in the form of interactive installations. Several types of activities, including nature hikes, could become the ash hill’s new purpose.

The monumental ornament on the Auvere power plant was taken down due to its suggested resemblance of the Soviet red star, while the local community interpreted the symbol as an electricity spark. In their reframing suggestions, the case study group proposed using the separated elements of the ornament to create an open air museum-monument

Reframing the 1872 Strike monument, the case study group aimed at emphasising the struggle for social justice championed by the Kreenholm workers. On the other hand, engaging the local community was also crucial. To achieve both objectives and preserve the monument, the group conceptualised several models that involved opening up the monument’s area for public, interactive and informative installations, as well as a weaving workshop with a far-reaching goal of strengthening the ties across generations and cultures among locals

In addressing the issue of the Sillamäe war memorials, the case study group members referred to their own international experiences and responses from local residents. Based on this combination, the group suggested replacing the monumental portraits of the Soviet servicemen with mirrors. That way, visitors could reflect personal family stories through themselves.

A key theme that emerged from the workshop was the importance of engaging local communities and transparently reconceptualizing contested heritage rather than erasing it. As demonstrated by the case studies, dissonant heritage—whether monumental sculptures or industrial waste—holds the potential to foster dialogue between cultures, generations, and historical perspectives. Through artistic interventions and community engagement, these objects could be transformed into spaces for leisure, tourism, and reflection. The knowledge and ideas developed at the workshop could benefit both Estonia and other countries grappling with their own dissonant heritage.

At times, one has to quite literally mind their steps and avoid pitfalls when approaching the dissonant heritage.