Team members: Diāna Meldere, Natali Käsk-Nõgisto, Gytis Dovydaitis, Alberto Governo, Eglė Jasaitytė, Kora Równicka.

Mentor: Triinu Väikmeri

Case study overview by Triinu Väikmeri:

Narva Kreenholm 1872 Streik Monument

Year of completion: 1972

Address: Ida-Viru county, Narva, Joala 17A

Sculptor Kalju Reitel, architect Boris Kalakin

Not protected as a monument

Kreenholm Manufactory

The construction of the Kreenholm manufactory belongs to the early days of the industrial revolution in Estonia. Narva’s powerful waterfall made it possible to use cheap water energy, and so a cloth and a linen factory were built there at first. At the end of 1856, Ludwig Knoop, who had moved to Russia from Bremen and enriched himself with the sale of English mechanical engineering products there, bought the island of Kreenholm with a closed cloth factory on the banks of the river.

In April 1857, the cornerstone of the first industrial building of the new enterprise was solemnly laid, while the construction of economic buildings and workers’ housing began. The factory was completed in a year and a half, and in October 1858 the first workers began their work.

In 1862, the spinning and knitting factory was completed, and the waterfalls of Narva launched three huge water wheels, which started the company’s machines. In 1868, waterwheels were replaced by modern water turbines, which for more than 25 years were among the most powerful hydraulic machines in the world.

The company’s growth was facilitated by its proximity to the port of Narva and the Tallinn-

St. Petersburg railway connection, which was opened in 1870. The factory mainly used cotton brought from America. Yarn, cotton thread and various cotton fabrics were sold mainly to Russia as finished products.

In 1870, a new spinning factory started operating, and slowly, with the launch of the Joala factory and the Georgi factories, the Kreenholm manufactory became one of the largest cloth factories in Europe by the end of the 1890s.

The start-up of the factories of the Kreenholm manufactory was accompanied by the rapid growth of the working population. In 1866, more than 2500 people worked in the spinning and weaving factory, and in 1872 there were more than 4600 workers in the factories (3250 of them Estonians and 1400 Russians), which made the Kreenholm manufactory the largest company in Estonia. About 800 construction workers were added to them (a large number of construction workers built a canal for Joala housing).

The 1872 Strike

In the summer of 1872, a cholera epidemic broke out among the Narva garrison and then among construction workers, which spread throughout the city. The epidemic became one of the drivers of the strike, as more than 500 people fell ill in Kreenholm alone and more than 330 people died in a short time, which was a lot for a city the size of Narva.

But life of the manufactory worker was tough even without the epidemic. By the early 1870s, working conditions became extremely difficult: over time, the working day increased from 12 hours to 14 (work started at five o’clock in the morning and lasted until half-past nine in the evening), the breakfast break was abolished, the lunchtime lasted an hour and since no food was allowed in the factory, then those who didn’t make it home for lunch had to eat a piece of bread outside the factory on the bridgehead. Piecework pay was cut and new fines were imposed (for breaking some parts of the machine, a worker could be fired, not fined), the length of the so-called average piece of fabric increased somewhat, 2% of the salary was deducted for church and hospital expenses, etc.

While the previously built residential barracks featured even lighting and some modern central heating and plumbing, more than 900 new workers were placed in buildings that were converted from the stables and barns of Joala Manor, with up to 20 people living in some rooms.

During the epidemic, the manufactory hospital no longer accepted all those in need. The sick lived with the healthy, which accelerated the spread of cholera. The panic was aggravated by rumours that someone had sprinkled white-colored powder into the Narva River and thus poisoned the water.

The director of the factory, Ernst Kolbe, ordered that the windows be kept open to ventilate the buildings under the threat of a fine. This was accompanied by draughts and illness of sweaty workers. In addition, in order to prevent the epidemic, the factory’s direction began to distribute pepper- vodka to workers before lunch.

The workers became restless. On August 2, 1872, riots broke out, as 200 construction workers demanded immediate dismissal in order to escape from the looming cholera. The stonecutters left their passports in the office and left without a final bill.

On August 7, factory workers protested against the opening of windows, and Director Kolbe gave in. At the same time, the workers put forward as their main demands the reduction of the working day to 12 hours (starting work at half past five), an increase in wages up to 15 percent, the lunchbreak lasting for an hour and a half, the abolition of the 2% deduction from wages, etc. Among other demands the most important was, perhaps, to allow the working children more time for education. Kolbe promised to forward the demands within a week to the main shareholders of the Kreenholm manufactory – Knoop now lived in Bremen, others in Moscow.

Since Mr Kolbe did not have the appropriate powers for decision making and he summoned the factory owners to solve this problem, the demands were not quickly met and at least half of the men who worked on the construction of the river canal also began a support strike on August 9.

After a week, in August 14, Kolbe had not responded to the demands made. About 500 weavers from about 4500 workers interrupted work and, through ten representatives, made their demands, which were summed up by nine points. Kolbe again asked for a week to respond to the demands, hearing that if the demands were not met, the entire factory would begin a strike. In the days that followed, weavers urged spinning workers — who made up two-thirds of the entire working class — to work out and make their demands. On August 18, 12 weavers at the factory office warned that if they did not comply with the demands, they would go on strike on Saturday, August 19.

The factory government asked the Governor of Estonia and the gendarmerie government of

St. Petersburg Governorate for help and protection. On August 20, 1872, a presentation of the strike was made to Emperor Alexander II. The situation was visited on the spot by the polkovnik of the gendarmerie government, who talked to the workers, the governor who arrived from Tallinn, and the arrival of the directors-general was expected.

On August 21, 1872, an agreement was concluded between the workers’ representatives and the factory manager G. Kolbe. The governor of Estonia, Mikhail Shakhovskoy-Glebov-Streshnev, the commander of the St. Petersburg gendarmerie government, Birin, 40 representatives for the weavers and 20 for the spinners were present at the conclusion of the agreement. Most of the workers’ demands were satisfied, with the exception of the issue of wages, since it depended on market prices, and personal issues, because it was not appropriate to resolve them by a “political” decision at such a level. The agreement was confirmed and agreed to by Baron Ludwig Knoop, director of the Kreenholm Manufactory. On August 22, 1872, the weavers set to work again.

The negotiations lasted all day. Then the three directors-general, the governor and the gendarmerie commander, and on the other hand, the workers’ representatives, signed two agreements, separately with representatives of weavers and spinners. Both agreements were drawn up in both Estonian and Russian.

The management of the factory agreed to make certain concessions: start the working day at 5.30, extend the lunch break to an hour and 15 minutes, change the system of fines for broken machine parts, not to be fined for absence for a reason and to stop withholding 2% of the salary.

It was necessary to dismiss the working elder Peeter Säkk and elect a new elder by the workers. The salary was not increased, the hated velsker remained in office, there was no agreement about increasing the time of childrens school attendance. Following the signing of the agreements, the spinners-weavers began their normal work on August 22.

Kolbe then tried to remove the leaders and instigators from their jobs. Thus, a letter of request from the workers was drawn up, thanking the factory government for meeting the requirements and asking for the removal of seven workers from the factory – who, judging by their names, were all Estonians. The letter was signed – in Soviet terminology – by a “group of sole-lickers”. An attempt to collect signatures on a letter of complaint in a tavern caused a new discontent among the workers, who were now seeking help from a local gendarmerie major.

On September 9, Kolbe had Villem Preismann and Jakob Tamm along with 4 other workers who wanted to travel to Tallinn to complain about the factory’s management, imprisoned by a judge in the Hague. They were sentenced to seven days’ imprisonment in the prison house of the Narva magistrate, the formal reason being an incident that took place a few days earlier in the house of the ruler of the Kreenholm manufactory, conserning the collection of signatures in the tavern.

In the morning hours of September 11, a new strike began, which swelled in succession. The strikers equipped with cuddles blocked the path leading to the island of Kreenholm, stopping the rest of the workers from going to work, and demanded the release of those arrested.

Around noon, about 300 striking workers made their way from the Narva River Bridge to the city’s town hall, where the prison was located. Meanwhile, a Hague judge along with police cordons tried to free the bridge while the strikers attacked them with stones. Although the police managed to arrest some of the strikers, they were soon freed from the manufactory’s prison cells by other workers. In the course of the subsequent looting, the Kolbe residential building was also damaged.

In the evening, a local 220-man troop under the command of Polkovnik Reinvald arrived. Governor Shakhovskoi, who arrived at the site, asked that in addition to the army guarding the factory, auxiliary forces from Jamburg to St. Petersburg Governorate would be sent. By September 13, with the help of the soldiers from Jamburg, the situation was firmly under the control of government troops. On September 14, the work of the factory partially resumed. Subsequently, 35 activists were arrested, and the army occupied the area of workers’ houses. The strike ended on September 18 and the army left the factory on September 19.

An investigation followed, to find out the causes and participants of the disturbances. In October 1872 a court was held in Tallinn. 27 workers, mostly Estonians, were sentenced to forced labor, imprisonment, turmoil, or settlement. Prisoners sentenced to settlement and forced labour stood in disgrace in front of the City Hall in Tallinn on 25–26 November, while some of the convicts were later replaced by caning sentences. The commissioners of the August strike, Villem Preismann with his companions, were released from custody but were not taken back to work at the factory.

Already in September 1872, the owners of the Kreenholm manufactory, through Kolbe, sent 10,000 rubles to the governor of Estonia for use at his discretion for the “happy end of events”. The governor reported the stabbing to the gendarmerie, which considered it inappropriate to accept the money.

The court investigation concluded that the disturbances had no political motives, and the events that took place must be attributed to the incompetent management of the factory by its administration. Director Kolbe was soon removed from the factory’s management.

The concessions made by the strike were largely valid until 1897, when the organisation of work was significantly changed.

Workers’ demands in August 1872:

- Allow lunch to be held for 1,5 hour instead of the current 1 hour.

- Allow work to start at 5.30 in the morning instead of the current 5.00.

- To pay 40 kopecks for a 50-inch piece of fabric.

- To be fined for breaking a machine part according to its cost.

- For poor work and low labor productivity, not to be fined, but dismissed from the factory.

- “Eliminate” the factory’s hospice velsker Palkin.

- Replace Peeter Säkk, who is in the position of “starosta”.

- Not to make deductions from the account book without the consent of the owner.

- Allow working children more time to go to school.

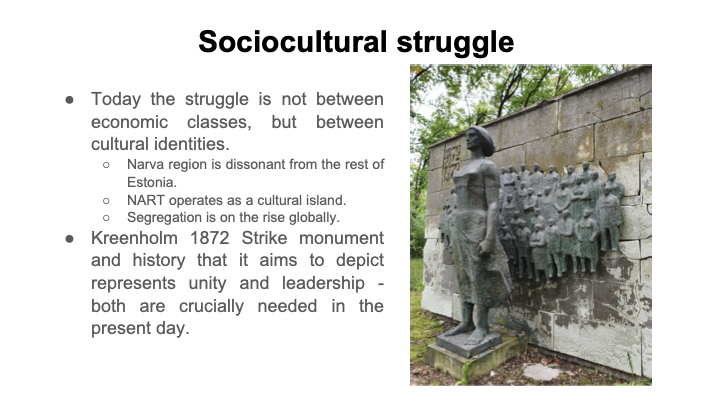

The Kreenholm strike was one of the largest workers’ withdrawals of that time in the Russian Empire and among its participants, V. Gerassimov, V. Preisman, D. Alexandrov and F. Afanasyev developed into eminent revolutionaries. According to the Soviet conception of history, with this first great struggle of the Estonian and the Russian working class, a decades-long continuous series of events in the class struggle began, culminating in the overthrow of the hated exploiters in the summer of 1940. In the same spirit, anniversary speeches were held and pieces of writing were published in the press until the mid-1980s.

During Soviet era, at least two books have been published about the event – Peet Sillaots “The Kreenholm strike of 1872” (1952) and on the 100th anniversary of the Great Strike, Pavel Kannu’s review “Kreenholm strike 1872” (1972). One should of course remember, that works published during Soviet era, must be read critically. Both books emphasized that the Narva strike was an event that encouraged the workers of St. Petersburg, the capital of the tsarist state, and other cities to continue their active struggle. The latter, of course, can be doubted, because according to Sillaots, only one Moscow newspaper published an editorial on this topic entitled “Disorder among workers in the Kreenholm manufactory near the city of Narva” and a couple of short notices in one St. Petersburg newspaper. The rest of the information still moved verbally around great Russia.

The manufactory, which employed 11,000 people at the end of the Soviet era, finally closed its doors in 2010. The loss of thousands of jobs created serious social tensions in Narva.

The monument

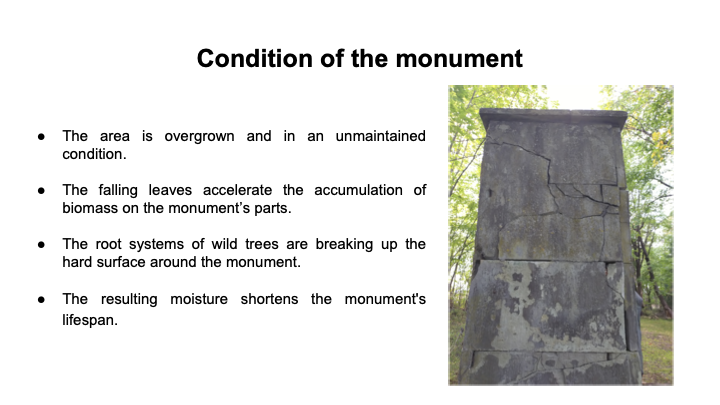

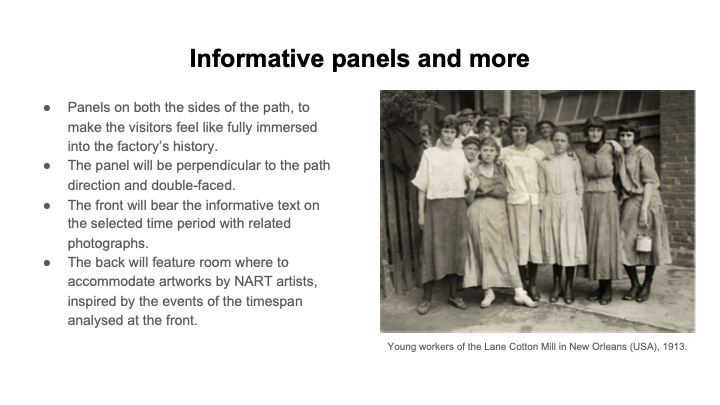

The Kreenholm 1872 Streik monument was erected for the 100th anniversary of the strike in 1972 and is located next to the pedestrian entrance of the Kreenholm manufacturing company in a forest park, which masses of workers passed on their daily commute to the manufactory. At the time of erection of the monument, Estonia was part of the Soviet Union, where working-class citizen were held in high esteem, so one of the means to propagate such an ideology was the creation of monumental artworks depicting heroic workers. Though during the strike, majority of the employees were men, a hundred years later, while erecting the monument, Kreenholm had mostly women workers, thus there is a woman depicted at the forefront of the monument.

At the present day some see the monument as just another typical „Red monument“, but some tend to believe, that the idea behind the monument was the opposition to child labor.

Additional reading

https://2021.muinsuskaitsepaevad.ee/en/exhibitions_post/1872-aasta-kreenholmi-streigi-monument/ (in English)

Last articles are mainly added to help understand the meaning of the strike in the present day:

https://naised.vikerkaar.ee/uncategorized/naised-tehastes-ja-barrikaadidel/ (in Estonian)

https://news.err.ee/1608739129/piret-karro-let-s-rename-narva-s-gerassimovi-tanav-after-amelie-kreisberg (in English)

Students’ results and presentation: