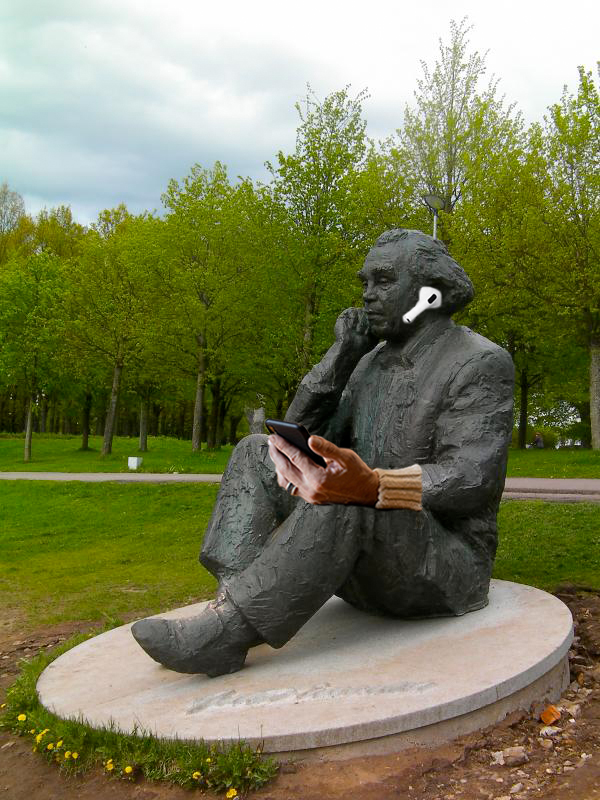

Uncontactable Gustav. Intervention of an anonymous art student from the course Art and Public Space, Spring 2024.

I teach a course at EKA on Art and Public Space which on the one hand deals with monuments, interventions and street art in urban space, and on the other hand looks more broadly at the position of artists and artworks in society. In this course, I also engage students in debates on topical issues (such as the removal of the Narva tank monument), theoretical issues (such as the problem of the legalisation of street art) and art historical case studies (such as Holocaust memorials). As few students have engaged in debates during their school years, they often start off in a bumpy way, but suddenly take off and the parties get into a heated debate. In a playful debate, even the timid speakers’ vocal cords are loosened, and emotional or even rude arguments may slip in later.

Often we laugh heartily, but sometimes what is said in a role can hurt. In one such debate, a student snapped that if Estonian Russians support pro-Russian monuments, they shouldn’t live here. Some of the students winced at this and lost interest in joining in the debate. I took over the debate and tried to explain why generalisations are dangerous – and intellectually lazy. As a lecturer, such moments are key. I can guess why a first-year student thinks like that, but if he or she has a similar opinion after graduation, something has gone wrong.

At the end of the lesson, when analysing the debates, I encourage students to view these debates as equivalents of larger societal debates. If, in the course of a debate, a student fails to convince his or her fellow students that Neeme Külm’s “Wave Poured into Concrete” would be a better solution for Tallinn Bay than Tauno Kangro’s “Kalevipoeg”,[1] how is he or she going to do so on a national broadcaster’s talk show, in an opinion piece, in an arts commission, or in a conversation with a family member or neighbour? Students are amazed at how easy it is to put forward populist views and how difficult it is to stand up for ethical or aesthetic principles that seem so natural among ‘their own people’. The lecture course alsos include essays by humanities scholars and artists on controversial issues in society (whether it be the erection of a War of Independence memorial or the removal of Soviet-era monuments). These are good texts, and there are many of them, but unfortunately even the most powerfully argued articles have not been able to avoid controversial political decisions.

*

In their work, art researchers and heritage conservationists are tacitly guided by their own Hippocratic Oath, devoting all their energy and judgment to helping works of art and cultural heritage and to serving the principles of humanity.[2] While some works may be off-putting (such as the tank monument mentioned above), even works with complex content must be preserved to ensure that the dialogue with their counterparts continues in ten, 100 or 1000 years’ time. The analogy with the medical oath is apt, for just as the principles of art history can vary over time and space, so too have the Hippocratic Oaths. The medical profession, for example, has changed from its former duty to preserve life to a focus on science and the importance of taking into account the wishes of the patient.[3] Something similar has been happening in the last few decades in the field of art history and heritage conservation, where humanitarians informed by postmodernism, visual culture studies and general societal change are increasingly critical of the autonomy of works of art and the take-it-or-leave-it style of conservation.

*

The post-Soviet period has been periodised by many scholars as three phases, roughly corresponding to decades. The first phase of post-socialism was a period of transition, during which both old and new practices coexisted. Despite the fact that some old hierarchies of values remained firmly in place, there was a rapid westernisation and neoliberal modernity was seen as the universal future. The debate on the Soviet legacy was largely based on totalitarian assumptions and focused on traumatic experiences. In the second phase, which coincided around the 2000s, the complete failure of socialist modernisation became apparent and Eastern Europeans were confronted with a negative image of the former Eastern bloc, which led, inter alia, to widespread manifestations of nationalism. The third phase of post-socialism in the 2010s signalled a generational shift, which led to a shift in memory politics. A generation with few memories of the Soviet period had entered the scene. Soviet-era art, design and architecture became popular. Memories and experiences previously considered inappropriate were normalised. Gradually, tensions settled and for years the ‘Red Monuments’ were not even mentioned. It could even seem that time had done its work.

However, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 turned the Estonian landscape of memory upside down again, and the Soviet monuments were once again out of place. The problem, however, is not the monuments per se, but the unresolved issues, which even the removal of the memorials will not solve. We therefore need meaningful debates around monuments. Since life has shown that monumental disputes alone are not enough, we must also have a say in the monuments and the visual culture that surrounds them. Let us try here to believe and support the maxim that a picture is worth a thousand words. Perhaps, however, if we leave the monuments in their place and imagine a new frame around them, both in image and in word, we will avoid conflicts that, in the worst case, will escalate into monument wars?

Gregor Taul

Accompanying the post are the interventions created within the framework of the Art and Public Space course of the first year of the fine arts undergraduate course at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

[1] The Kalevipoja saga ended with the Technical Surveillance Authority collecting opinions or competing petitions in 2016 regarding the installation of the sculpture in Tallinn Bay. The Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia submitted a competing application – a preliminary design for Neeme Külm’s sculpture “Sea Wave Cast in Concrete”. The work consisted of a 25 m2 and 50 cm thick square underwater concrete form, which ideally contained seaweed. Choosing between a 24-metre-high bronze statue and a metaphorically empty pedestal led to an absurd debate, and eventually Kangro’s interest in the project waned. For more information, see Eesti Ekspress 26 VIII 2016. https://ekspress.delfi.ee/artikkel/75167759/kangro-planeeritava-kalevipojaga-asub-voitlusse-betooni-valatud-merelaine (accessed 4 IV 2024).

[2] The Hippocratic Oath, Wikipedia 31 X 2019. https://et.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hippokratese_vanne (accessed 4 IV 2024).

[3] Reporter’s Hour. End-of-life will. To whom and for what?, Vikerraadio 3.IV.2024. https://vikerraadio.err.ee/1609288409/reporteritund-elulopu-tahteavaldus-kellele-ja-milleks (accessed 4.IV.2024).

***

Ako Allik

Intervention (Neeme Külm’s concept “Sea Wave cast in Concrete”)

During this spring semester, we were confronted with a controversy around Tauno Kangro’s proposal to build a monumental statue of Kalevipoeg. In response, a delegation from EKKM led by artist Neeme Külm proposed an alternative project for the competition, which would have seen 25 square metre concrete platform. The concept was to create a sense of an object invisible to the eye. The monument would have been invisible from the shore and could only have been identified by the information board and tthe waves breaking on the surface of the water.

Neeme Külm’s idea attracted attention because it raises the inevitable question of the necessity of this type of ideological monument. When you create a physical object that is impossible to see with the naked eye, you get a kind of Schrödinger effect, where in the end you don’t know for sure whether the monument is on the seabed or not. If the whole effect of the work is, from the outset, based solely on the imagination of the viewer and his or her theoretical understanding that there is a monument somewhere, then could we not not build a monument at all and agree as a society that there is a point in Tallinn Bay that we are all aware of and that means something to us. In this way, both the expenditure of resources and the endless disputes in society could be saved, as such an idea-based acknowledgement of something would cost nothing and would not disturb anyone.

In order to illustrate the ambiguity and in some ways the irony of the whole situation, I decided to make a performance video in which I take part in a competition and propose myself as an underwater sculpture in Tallinn Bay. The idea of the performance is to raise the question: if there is proof that someone was placed underwater as a sculpture and was not seen coming out, can we, like Neeme Külm’s work, ideally assume that they are still there? And even if the person did emerge, could we perhaps accept the fact that the sculpture existed physically only at the moment when the person was underwater, and that the point in Tallinn Bay will continue to exist as an imaginary sculpture of a man submerged?

***

Aliisa Ahtiainen

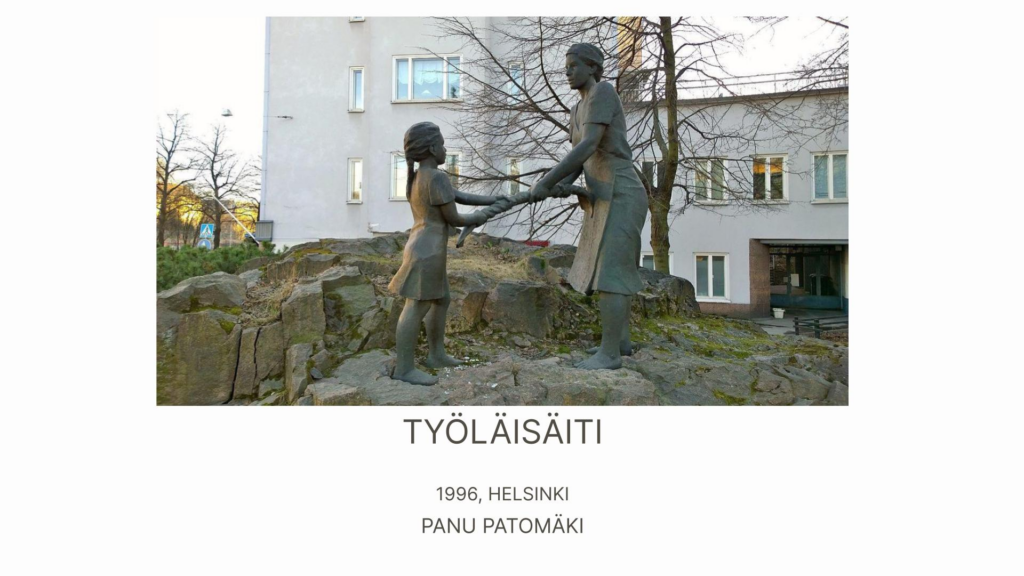

Working Class Mother

When I moved to Helsinki I was 20 years old and just starting my own life. In the neighbourhood I lived in, there was this statue of ”Työläisäiti” (working class mother). I remember it making me feel somehow really uncomfortable.

When I started to think about this intervention, I suddenly remembered this statue. The monument depicts a mother and a young girl who are twisting laundry to get it dry. The statue was unveiled on Mother’s Day in 1996 and it was ordered by the people living in this traditionally working class neighbourhood.

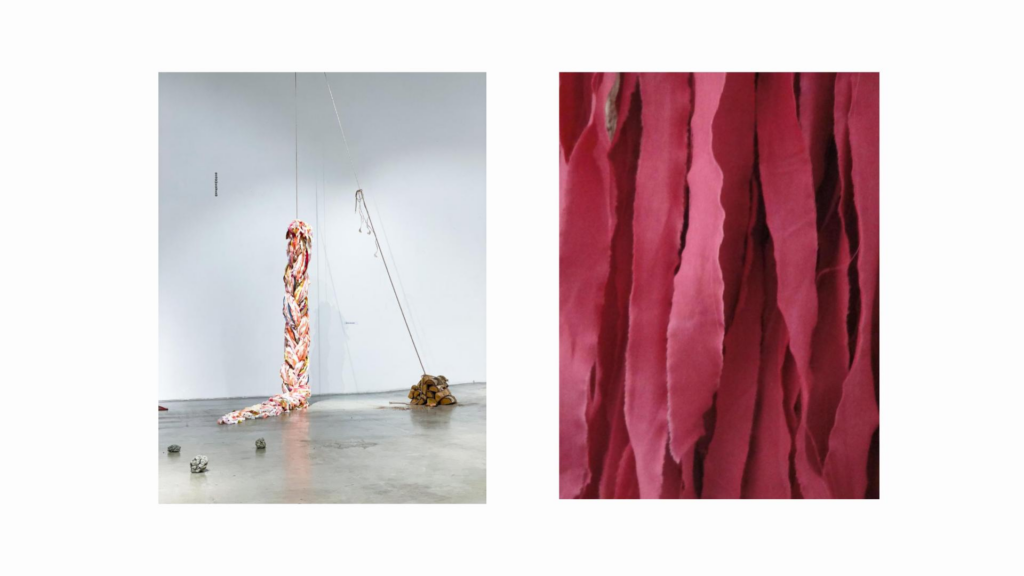

Last semester in our Sculpture and installation course, I made my finishing work with a large paper braid tied to a pile of logs. My aim was to comment on the connection between me and my mother as well as the relationship between daughters and their mothers in general. This topic goes so well together with the statue that I decided to use the same theme of braid.

In the intervention the plan is to cover the girls braid with colourful strips of fabric and wrap them around the laundry to make both the girl and the mother hold it.

I believe the image this creates is quite easy to interpret as a fight for independence and personal space. The mother is pulling the daughter’s hair, a part of her body, and the daughter is pulling it back. The tension is obvious.

The images and monuments that surround us may in some ways aim to create reality but they also have the power to estrange those who do not recognize the images. There are countless statues and monuments dedicated to mothers and children. They aim to create a communal belief of a good, innocent and selfless mother who is the backbone of our families and societies.

With this intervention I wanted to comment on the mythical mother. To bring into the public space a reminder that the relationships between children and their parents are rarely simple. I think it is important that this reality is acknowledged in public space. It has the potential to give the feeling of being seen to people whose own experiences of mothers and parents are less than ideal. It can also be seen as a fight between past and future, what is it that holds us back as individuals but also as societies?

***

Olga Dubrovskaya

To the Brave and Courageous

In Tallinn, on Pirita road, there is a memorial dedicated to Charles Leroux, designed by Mati Karmin, entitled “To the Brave and Courageous”.

On 24 September 1889, the American-born acrobat and experimental balloonist jumped from a hovering balloon over Tallinn despite adverse weather conditions and the opposition of his manager. A strong wind carried him towards the bay below, in full view of the spectators. It is said that one of the spectators died of a heart attack on the spot. Two days later, fishermen found his body, which was buried in the Kopli cemetery.

The intervention consists of attaching a parachute to an existing sculpture. The parachute is printed with the design of an organ donor card. On the one hand, the intervention aims to shift perspective and, instead of praising ‘courage and determination’, to make the viewer reflect on the consequences of foolish acts. On the other hand, the intervention could generate a public debate on organ donation, which is still to some extent taboo. In organ donation, it is important that people discuss it among themselves – without prejudice and with courage. In Estonia, after a person’s death, the discussion always takes place with the next of kin. They are asked if they know how the deceased felt about organ donation during their lifetime. This moment is often extremely difficult because of the grief involved, which is why it is good if donation has already been discussed in the family circle.