Article originially published on Estonian National Broadcasting (ERR) online news platform on 23rd November 2022

Every war grave is a monument to the horrifying consequences of human stupidity. Every war grave is the grave of every war. In retrospect, there is little we can do. We can offer peace to the memory of those who had to end their lives so senselessly and prematurely.

Recently, the public was informed that a secret commission had initiated the process of reburial of remains from 133 World War II burial sites (79 of them “depending on circumstances”). Let us open up the cultural contexts.

Mati Unt and the Decayed Bones of Lydia Koidula

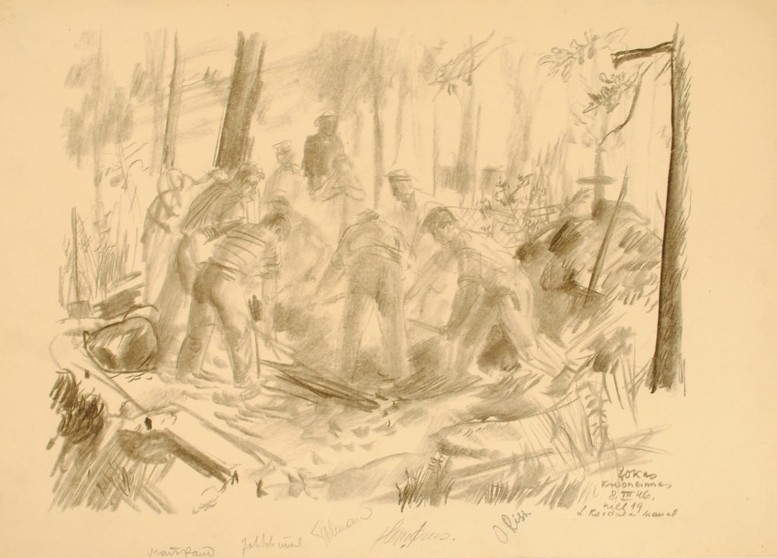

One by one we pick up the decayed bones while, up on the rim of the grave, the prominent party official comrade Smirnov, prominent members of the Naval Forces, comrade Kadasadze, and a slew of other Kronstadters – true aficionados of poetry – read, with great devotion, Koidula’s poems in faultless Russian translation, from her poetry collection recently published in Moscow.

Mati Unt, Diary of a Blood Donor, 1990 – Unt is quoting Mart Raud’s memoirs (In English: Mati Unt. 2008. Diary of a Blood Donor. Translated by Ants Eert. Champaign, IL: Dalkey Archive Press. Translation altered.)

In the 1980s, the writer Mati Unt was deeply influenced by gruesome, naturalistic descriptions of Lydia Koidula’s reburial — so much so that they found their way into both his play The Hour of Spirits on Jannsen Street and his novel Doonori meelespea [Diary of a Blood Donor].

The plot of Diary of a Blood Donor proceeds from the injustice of the reburial: Koidula’s husband, Michelson, who was left behind, buried in the Kronstadt cemetery, turns into a vampire to seek revenge on the Estonian people. However, upon arriving in Estonia, Michelson softens, begins to support Estonia’s struggle for freedom, and concludes that he must seek the blood necessary for his vampiric existence only from a blood transfusion station.

Mati Unt had read descriptions of Koidula’s reburial from decades earlier; he was not personally present to collect the decayed bones. However, Estonian politicians might reflect that Unt’s depiction serves as a reminder of the physical, decaying-skeletal reality of death and graves. Grave desecration is not just an administrative command written on paper; it is an abject, corporeal act carrying a heavy ethical weight.

The digging up of the ashes of Lydia Koidula from the German cemeteryin Kronstadt 8. VIII 46. by Evald Okas (Parnu Museum Art Collection)

Juhan Peegel and the Senseless Deaths of World War II

On April 7, 1978, the weekly Sirp ja Vasar began publishing Juhan Peegel’s novel I Fell in the First Summer of the War as a serial. The novel shocked readers with its frankness, which was then unprecedented in Soviet literature: the first-person narrator, Jaan Tamm, an Estonian soldier who perished in the first summer of the war, tells his own story – the story of a young man’s meaningless death.

Jaan Tamm – like the novel’s author, Juhan Peegel – was drawn into the war from the Estonian Republic’s conscript service. It is well known that after the Soviet occupation of Estonia, the military was reorganized. The Estonian Army was transformed into the 22nd Rifle Corps, in which both Juhan Peegel and his fictional protagonist Jaan Tamm found themselves.

Peegel himself had initially enrolled in the University of Tartu in 1939 to study Estonian language and literature, but was sent to military service in October. As a boy born in 1919, that was all that was necessary to send him into the Red Army.

The novel details how the bulk of Estonian soldiers were formed into a combat artillery unit: in addition to local recruits, they were joined by young, inexperienced conscripts mobilized from Russia, at least half of whom were untrained. The unit’s equipment was a chaotic mix of World War I-era weaponry, German-style backpacks, German WWI-era helmets, and Estonian military uniforms stripped of their original insignia and replaced with Soviet badges.

The narrator of Juhan Peegel’s novel falls in the very first summer of the war. The fallen soldier describes his burial as follows:

“I don’t know who had already managed to pull off my sturdy leather boots with spurs, and take my belt. My clothes were no longer salvageable; they were caked with blood, especially my shirt. Because of that, my pockets had been left untouched, as were the photographs they held within. There was one photo from my school graduation days, another from my time as a soldier – still in Estonian uniform, and one taken with my comrades at a street photographer’s stand on our way to the front. There was also a picture of my sweetheart – a beautiful, slightly sepia-toned photo – and the last letter from home.”

Jaan Tamm was sent into battle on a suicide mission – as were an unthinkably large number of other Red Army soldiers during World War II. The novel describes many such scenes, including this one:

“Then comes a precise and dense barrage on the battery positions. A single avalanche of mortar explosions. Rotten slats of fencing, clumps of earth, and potato vines fly into the air. The whistling and cracking of shrapnel against the artillery, the rustling in the bushes.

Then comes silence.

The battery is no more.”

To read Peegel’s novel today is to hear the echoes Russia’s current war of destruction in Ukraine. One hears again the themes of poor equipment, lack of coordination, inadequate troop training, the turning of young lives into cannon fodder, and a massive, senseless devastation. And again, the same results: ruined settlements and landscapes covered in graves.

Whose bodies lie in those World War II graves scattered across the vast theatre of war? Do the nationalities of these senselessly lost war victims matter? The Red Army drew from dozens of nationalities and ethnic groups; some fought with deep conviction against fascism; others, like Juhan Peegel, were simply caught up in circumstances far beyond their control.

Estonian soldiers’ burial sites can likewise be found in many places, and Peegel later regretted that there was little interest in Estonia in the graves of our fallen soldiers. All these dead were lost pointlessly, needlessly; because war is the greatest and most absurd futility humanity has ever conceived, a vast machine of destruction where thousands, hundreds of thousands, even millions fall; people who could have lived, and would have perhaps been happy.

Every war grave is a monument to the horrifying consequences of human foolishness. Every war grave is the grave of every war. Retrospectively, there is little we can do. We can offer peace to the memory of those whose lives ended so senselessly and prematurely.

At the same time, we might also understand that it is precisely this, the meaninglessness of death, that unites soldiers on both sides. And we might commemorate those fallen as if they were our own—Ukrainians, Belarusians, Kazakhs, Mordvins, Udmurts, Armenians, Estonians, Russians, and others who died in battles on Estonian territory.

Of course, these burial sites do not need to preserve Soviet-era rhetoric about “liberation,” but they could become places where all Estonians come together to remember those who perished senselessly in wars. Perhaps even with folk dances, a choir performance, and a speech by the mayor.

Which Crisis Are We Fighting Against?

Mihhail Lotman, a member of the Isamaa faction in the Estonian Parliament, stated on ERR that the issue of Soviet-era symbols is not a priority for Isamaa — in his opinion, the Narva tank could have been left in place and painted in rainbow colors. Yet, the “monument offensive” is being pushed by Isamaa’s Minister of Justice, Lea Danilson-Järg, with Foreign Minister Urmas Reinsalu (also from Isamaa) backing her up.

Surveys have shown that the Estonian public does not perceive the monuments as a security threat. Even Isamaa, as Lotman would have it, is not particularly interested in the issue. One gets the strange impression that some kind of machinery has accidentally been set in motion, grinding away mindlessly under its own inertia, stirring up mud that everyone finds unpleasant, but no one has found the energy to bring this to a halt.

This is a call to the secretive, name-protected Estonians, members of the monument committee, whose lives, according to our government, are in danger, in democratic Estonia: pull yourselves together and put an end to this absurd process. You have – surely against your own will – become a stain on democratic Estonia. In Estonia, no member of a state committee is threatened with death, kidnapping, or torture. Even your personal raccoons are in no danger of being stolen.

We are facing multiple crises, on a massive scale. Our house – our state – our planet – is on fire: a climate catastrophe is approaching, we have tens of thousands of war refugees for whom we must try to create humane living conditions, our people are becoming poorer, inflation is soaring… And yet, our government wants (or perhaps does not really want?) local governments to engage in disturbing the peace of graves where the dead have rested for decades.

One must also ask how exactly this process is supposed to take place. One hopes it is not with an excavator’s bucket tossing buried bodies and skulls into disarray. Perhaps, as Mati Unt described: one by one, we lift decayed bones from the soil while, at the grave’s edge, leading officials – Lea Danilson-Järg and others (whose names remain shrouded in deep secrecy, for security reasons, of course) – devotedly recite poetry.

But which poems? It’s doubtful that any Estonian writer’s work would be deemed appropriate, especially since the creative unions have been declared incompetent in this matter. Perhaps the esteemed commission itself will compose the solemn verses.

It would be deeply cynical to delegate the shifting of bones and the desecration of graves to local governments.

Hence, a call to local governments: if the monument committee’s decision does indeed receive government approval, then summon Lea Danilson-Järg and all the politicians who voted in favor of it to carry out the work themselves. Not to stand solemnly at the graveside reciting poetry, but to physically violate the remains of war victims, to remove these remains from their resting places with their own hands. To sneer over the young lives senselessly lost in a war decades ago. And to scorn the past grief of their loved ones.

Editor of the Estonian text: Kaupo Meiel

Translated by Uku Hughes

Cover image – a photograph of the reburial of Lydia Koidula in 1946 (Tallinna Kirjanduskeskus)

[1] Reference to the recent news of Russian soldiers stealing a raccoon from occupied territory in Ukraine.